Despite reservations about the military-industrial complex, and the disproportionate weight given to war storytelling, the story of Allan Underwood is worth telling. The details are provided by a web site for the 487th Bomb Group, which as of this writing is still holding reunions. As the site explains, the toll on U.S. airmen was considerable; the air battles cost 26,000 lives and 18,000- wounded — 10% of all U.S. deaths in the war. This group flew B-24H/J and B17G aircraft, and it lost 33 aircraft. Its bases of operation were farflung, including locations in Nebraska, New Mexico, Florida and New Jersey. In Europe, the base was Station 137 in Lavenham, Suffolk, England.

Like his four brothers, Allan was born in Nogales. As a young man, he moved to Los Angeles where he completed one year of college, and worked in a semiskilled occupation in the building of aircraft. He was single when he enlisted in the U.S. Army in Phoenix on 21 January 1943. The version of the story I know does not include details of his training, but we know this about air crew training:

Becoming a USAAF pilot during WWII wasn’t an easy, simple or quick procedure. To illustrate how difficult and dangerous the task was, consider that 324,647 cadets entered training between January 1941 and August 1945. 132,993 washed out or were killed during training. This attrition rate of nearly 40%, was due primarily to physical problems, accidents or inability to master the rigorous academic requirements. –WRAFS Museum, Arkansas

Allan’s experience would have been highly compressed. The group’s first combat mission was not flown until its control was transferred to England’s Eighth Air Force. That event took place in 7 May 1944.

Missions flown were not limited to Germany. For instance, the group flew numerous missions to attack V-weapon installations in France, marshalling points in Belgium and airfields in Holland.

From here, Paul Webber, who researched the history for the 487th Bomb Group Association, takes the story:

After training, he was assigned as navigator on the heavy bomber crew of Second Lieutenant Charlton A. Deuschle, in the 838th Bomb Squadron of the 487th Bomb Group. This Group was based at Army Air Forces Station 137, near the village of Lavenham, Suffolk, England, and was part of the 8th U.S. Army Air Force in Europe.

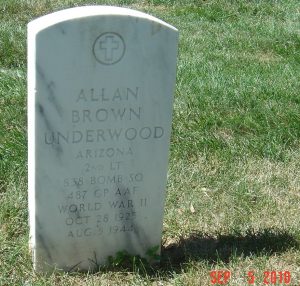

Lt. Underwood and seven of his crew mates were killed in action on 5 August 1944 while on a mission to bomb an aircraft factory at Magdeburg, Germany. Their aircraft, B-17G 43-38007 [which the crew dubbed “The Moldy Fig”], was shot down by flak during the bomb run, and crashed near Lostau, Germany, 13 kilometers southwest of Burg, Germany, just northeast of Magdeburg. Pilot Lt Deuschle and gunner Sgt Robert J. Crooker survived and became prisoners of war. The dead were buried initially at the village cemetery in Lostau. (Lostau is a village and a former municipality in the Jerichower Land district, in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Since 1 Jan 2010, it is part of the municipality Möser). After the war, Underwood’s remains were returned to the United States and re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. He is buried in Section 11, Site 253 LH.

There are a few other details. Survivor Sgt Crooker, who told relatives that he was “severely mistreated by German civilians” while he served as a POW, reported that their B-17G took a direct flak hit on the right wing and in its bomb bay 1-2 minutes before the start of the bombing run. Part of the wing came off and the aircraft exploded, all in a matter of seconds.

There are a few other details. Survivor Sgt Crooker, who told relatives that he was “severely mistreated by German civilians” while he served as a POW, reported that their B-17G took a direct flak hit on the right wing and in its bomb bay 1-2 minutes before the start of the bombing run. Part of the wing came off and the aircraft exploded, all in a matter of seconds.

German civilian losses from Eighth Air Force strategic bombing, while not associated with this particular mission, were at times consequential. For instance, a raid two months later on Duisburg, about 250 miles from the crash site, caused a firestorm and killed 2,500. Duisburg was a logistics center for the Nazis and a center for chemical, steel and iron industry at the time.

The war stories from Bill, John and Robert have not been a major part of family lore — at least not so far. From what has been determined so far, the Underwood boys were loyal, disciplined and answered a calling that — as wartime callings go — had a moral high ground.